What your face might reveal about your future children: scientists explore the surprising link between male features and child gender

What your face might reveal about your future children: scientists explore the surprising link between male features and child gender

A new scientific study suggests that a man's facial features may subtly predict whether he is more likely to father sons or daughters.

Russell Crowe (centre), who is best known for his roles in films such as Gladiator, has two sons - Charles Spencer Crowe (left) and Tennyson Crowe (right)

Many would argue that Jason Statham (pictured) has a dominant face. He appears in films such as The Beekeeper and Meg., His firstborn is a boy, called Jack, who he shares with Rosie Huntington-Whitely

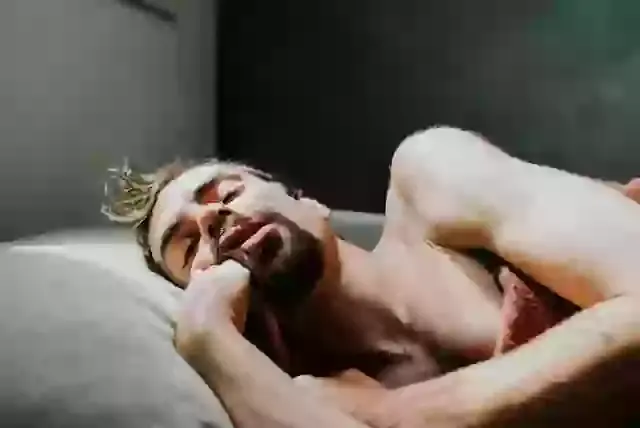

Many would argue that actor Tom Hardy has this particular characteristic. His son Louis is his firstborn child - which appears to confirm the study's findings

The mystery behind your baby’s gender: is your face a hidden clue?

For generations, people have speculated over what determines whether a child will be born a boy or a girl. From old wives’ tales to medical research, the fascination has never faded. But now, scientists are turning their attention to something unexpected: the father's face.

Could your jawline, facial symmetry, or overall masculinity hold the answer to your future child’s gender?

investigating the link: from facial structure to family structure

In a recent psychological and physiological study, over 100 heterosexual couples with at least one child participated in a unique experiment. The researchers focused solely on analyzing facial traits of the fathers—such as the strength of their jawlines, the symmetry of their features, and the overall appearance of masculinity.

Their goal? To find out if there’s a relationship between these traits and the likelihood of having a son.

The results were intriguing: men with more traditionally masculine facial characteristics were more likely to have sons as their firstborn. It’s a discovery that could add a new dimension to our understanding of genetics and attraction.

how might your face influence biology?

The researchers did not claim to find causation—but the correlation invites thought. One theory is that testosterone levels, which help shape masculine facial features, could also influence the sperm production process. More specifically, men with higher testosterone might produce more Y-chromosome-bearing sperm, which leads to male offspring.

This theory aligns with a broader evolutionary perspective. In certain societies or evolutionary environments, producing male offspring could have increased survival or reproductive advantages, leading to a potential biological “preference” coded over generations.

facial symmetry and its genetic story

Facial symmetry has long been associated with health and genetic strength. People with symmetrical faces are often perceived as more attractive, and science backs that up: symmetry may signal fewer genetic mutations and greater resistance to disease.

In this context, fathers with more symmetrical features might not just be seen as more appealing partners—they might also pass on genetic qualities that favor the birth of sons.

Another interesting angle is the concept of "facial averageness." Research suggests that people with features closer to the population average are generally seen as more attractive, possibly because these faces subconsciously suggest healthy, adaptable genes.

evolutionary psychology: the ‘sexy son’ theory

Evolutionary biologists often refer to the “sexy son hypothesis,” which suggests that females may instinctively choose partners with traits that would make their sons more desirable to future mates. This subconscious selection would theoretically increase the mother’s genetic legacy.

Masculine facial traits—strong jaws, prominent brows, symmetrical features—may have historically been signs of good genes. If a woman chooses a partner with these attributes, her sons might inherit them, making them more likely to attract mates and continue the genetic line.

This could help explain why certain physical traits in fathers might be subtly associated with having male children.

are looks really that powerful?

While the idea that a man’s face might influence the sex of his baby sounds dramatic, researchers are careful to stress this is just one small piece of a very large puzzle. A multitude of factors—from genetics and hormones to environmental influences and chance—all play a role.

That said, these findings do open an interesting door. They suggest that evolutionary pressures and subconscious mate selection could have more influence on our biology than previously thought.

what about other contributing factors?

This study focused solely on male facial features—but what about the mother’s characteristics? Or the impact of health, diet, stress, or environment?

Other research has shown that maternal health, stress levels during conception, and even seasonal changes might influence the odds of having a boy or girl. The combination of these factors with paternal features could one day give us a more comprehensive picture.

Further studies may also explore whether hormonal levels in both partners at the time of conception influence gender probabilities.

the limitations: what we don’t know (yet)

As compelling as this study may be, it comes with limitations:

-

The sample size was relatively small

-

Cultural and genetic backgrounds of participants may have influenced outcomes

-

The study only established correlation, not causation

This means we cannot definitively say that having a masculine face causes someone to have a son. We can only say that there’s a noticeable statistical link in this particular sample group.

More expansive research across different populations, age groups, and geographical areas would be required to validate and expand upon these findings.

could this change how we view fertility and reproduction?

The potential implications of this research are fascinating—not only for evolutionary biology, but also for modern reproductive science.

If physical traits are even slightly predictive of offspring sex, future fertility studies could integrate these indicators into broader data models. This might one day help couples better understand their chances of having a boy or a girl—though, for ethical reasons, it’s unlikely such information would be used to influence conception.

Instead, it may enhance our understanding of how deep-rooted biological cues shape our lives in subtle ways.

the social impact: do these findings change anything?

On a social level, it’s important to remember that all children, regardless of gender, bring equal joy, purpose, and value to families and communities. This study should not be interpreted as a reason to favor one gender over another.

Rather, it’s a fascinating glimpse into the hidden interplay of biology and physical traits—a reminder of how much we still have to learn about the forces that shape human life.

final thoughts: your face tells a story

From the structure of your cheekbones to the symmetry of your features, your face carries echoes of your evolutionary past—and, potentially, whispers of your genetic future.

While we're far from fully understanding the mechanisms behind how physical traits influence offspring, one thing is clear: our faces may reveal more than we ever imagined.

This new perspective blends science, genetics, psychology, and human curiosity, opening up exciting new paths of inquiry.

News in the same category

Experts reveal the effects on your body from eating one meal a day after a sh0cking simulation

Major medical breakthrough: Korean researchers discover “Undo” mechanism to transform tumor cells back to normal

If you often notice ringing in your ears, this might be a sign that you will suffer from ...

Drink water on an empty stomach right after waking up for 1 month and see how you transform physically and mentally

5 types of food that can do wonder for your gut health and digestion

Scientists may have uncovered the reason why weight tends to rebound after loss

The truth about cold water: 5 health concerns you should know

Early warnings signs and symptoms of ovarian canc3r everywoman should be aware of

8 types of food that can fight canc3r many of you didn't know

New injectable male birth-control provides protection for over two years, reports biotech firm

What happens to your bl00d pressure if you eat banana daily: The answer is not what you expected

For those who wake up more than 2 twice to urinate at night, it could be a sign of these serious health conditions

4 types of super common drinks that do more harm to your l!ver than alcoh0l but many people don't know

Early warning signs of diabetes: The reason why it is "the silent k!ller"

When heartburn and bloating isn’t normal: How to k!ll the bacteria causing havoc in your gut

Warning Signs Your Kidneys May Be Failing: 8 Symptoms You Should Never Ignore

Snakebite Season Is Here: A Comprehensive Guide on How to Respond Safely if B!tten by a Venomous Snake

Five warning signs of colon c@ncer revealed by top doctor as cases rise sharply among younger adults

News Post

The Hidden Function of the Small Hole in Your Nail Clipper

Family's Thyroid Tumor Discovery: A Cautionary Tale About Excessive Iodized Salt and Soy Sauce Consumption

Texas Woman D!es After Using Contaminated Tap Water for Sinus Rinse

4 Foods You Should Never Reheat: Health Risks Explained

Why Some Train Toilets Discharge Waste Directly onto Tracks

Easy Homemade Rice Gel: The Ultimate DIY Face Cream for Hydrated, Glowing Skin

With its powerful combination of rice, aloe vera, vitamin E, and tea tree oil, this cream not only nourishes the skin but also helps brighten dark spots, reduce fine lines, and promote youthful, glowing skin.

10 Effective Ways to Get Soft, Pink Lips Naturally: Proven DIY Remedies for Flawless Lips

By incorporating simple, effective DIY remedies into your routine, you can nourish, hydrate, and brighten your lips while enjoying the beauty of nature’s ingredients.

What Your Fingernails Reveal About Your Health: Insights from Experts

Fenugreek Water for Weight Loss: Methi Water Benefits and DIY Recipes

Fenugreek is a natural, affordable, and effective solution for promoting healthy weight loss and improving overall health.

A Heartwarming Flight: How Strangers Came Together to Help a De@f-Bl!nd Passenger

n an Alaska Airlines flight, a de@f-bl!nd man named Tim experienced extraordinary kindness from strangers - including a 15-year-old girl who used ASL to communicate. This inspiring story will restore your faith in humanity.

DIY Flaxseed Collagen Night Gel: A Natural Remedy for Hydrated, Youthful Skin

By harnessing the power of flaxseeds, aloe vera, and vitamin E, this DIY treatment helps to nourish, hydrate, and protect the skin, all while stimulating collagen production for long-term skin health.

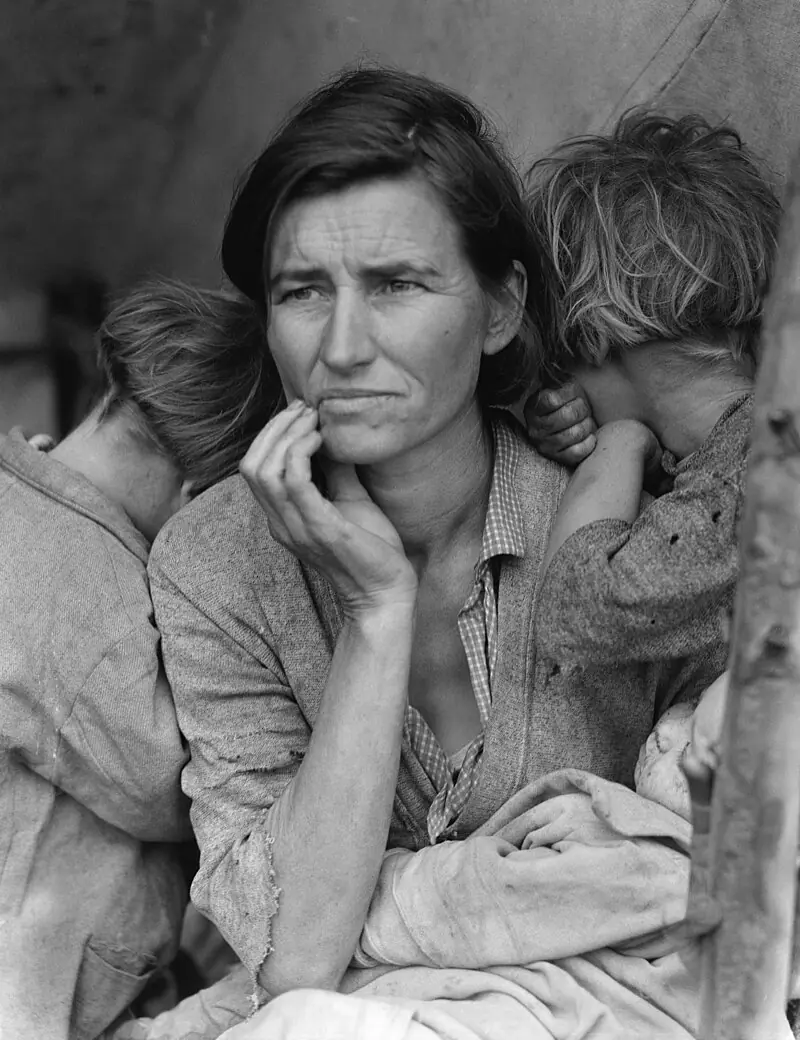

The Great Depression: How the 1929 Market Cra$h Reshaped the World

The 1929 market crash sparked the Great Depression, reshaping the world for decades. Explore its impact! ❤️📉

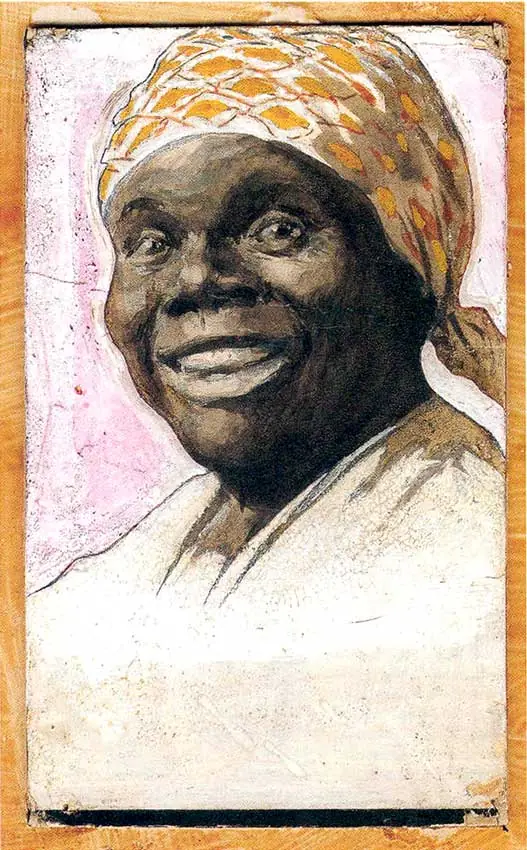

Unveiling the Real Woman Behind "Aunt Jemima": The Legacy of Nancy Green

Discover the powerful, untold story of Nancy Green, born into slavery, who rose to national fame as the original "Aunt Jemima." Learn about her resilience, contributions, and why her true legacy deserves to be honored.

5 Ways To Use Aloe Vera Gel For Glowing, Flawless Skin

Apply these masks and serums 2–3 times a week, and complement your skincare efforts with a healthy diet and plenty of water.

GAS STATION WORKER FINDS ABANDONED BABY - THEN FATE DELIVERS A MIRACLE

A man discovers a newborn abandoned in a box, setting the course for a journey of love, sacrifice, and healing. This story explores the transformative power of family, compassion, and second chances.

DIY Onion Rice Hair Mask To Boost Hair Growth

This simple, affordable treatment can be easily added to your regular hair care routine for noticeable improvements over time.

The Surprising Ages When Aging Speeds Up – What Scientists Have Discovered

A new study reveals that aging spikes at two specific ages, 44 and 60, and scientists have uncovered what happens to your body at these times. Learn the surprising results and what you can do to adjust.

Study Finds Sleep Habits Could Increase Your R!sk of Premature Death by 29% – Here’s Why

A new study reveals that poor sleep habits may increase the r!sk of premature de@th by up to 29%. Discover the sleep patterns linked to this danger and how you can improve your sleep health.

Expert Reveals Why Sleeping Without Clothes in Hot Weather Might Be a Bad Idea

Discover why sleeping without clothes during hot nights may not be as cooling as you think. Learn expert advice on how to sleep better in the heat.

New Study Reveals Alarming Rise in Anal C@ncer and Who’s Most at R!sk

A new study highlights a concerning rise in an@l canc3r cases, particularly among women over 65. Learn about the risk factors and what you can do to reduce your chances.